Big Island & Back: Ferries Steam Ahead!

Steam ferry Minneapolis, c. 1906

On warm summer days I often find myself on the boat headed to Wayzata. Here, I tie up to the pilings and climb the stairs toward the Wayzata Depot for an afternoon of volunteer work inside. While talking to visitors, I’m frequently asked about the Big Island Amusement Park and hear assumptions that the Yellowjacket steamers like Minnehaha must have been busy bringing tourists to their island getaway. Truthfully, this was not the case and folks are often surprised to hear it. So, if not the Streetcar boats, then what’s the story?

After the turn of the 20th century, the Twin City Rapid Transit Company was on a clear mission to monopolize the tourism industry of Lake Minnetonka. In the decades prior, the area had seen such a major tourism boom that even presidents had come here to compliment the lake’s beauty and healthful effects. Recognizing the opportunity the streetcar company, who was a major player in Minneapolis & Saint Paul’s outward development, wanted to capitalize on Minnetonka’s allure.

Starting in 1906, the company procured a handful of existing steamboats from Captain John R. Johnson who was already revered on Minnetonka for his heroism and reliability. Johnson saw the writing on the wall as the streetcar titan loomed over his community and seemed to take well to the old adage, “if you can’t beat ‘em, join ‘em”. Yet, the company had greater maritime ambitions for Minnetonka.

In the prior year, the company had already begun construction of their now infamous Streetcar boats and, in May 1906, launched all 6 of them into the lake. These boats bore the familiar names of the most successful streetcar lines in the Twin Cities: Como, Minnehaha, White Bear, Hopkins, Harriet, and Stillwater. These boats were destined to expand the company’s reach by offering routes to 26 locations around Minnetonka. Again, there were still greater ambitions. . .

Lastly, the company capped off its major Minnetonka investments for the year by their grand opening of Big Island Amusement Park. Ultimately, the hope was for the park to draw out regular tourism to Minnetonka via the streetcars. In a way, it’s very similar to what Disney’s Caribbean cruises do today. Guests board a Disney owned ship, sail to a Disney owned island, and oftentimes sail back to stay at Disney owned resorts. Likewise, the rapid transit company hoped to do the same. Ride out on a company owned streetcar, purchase tickets on a company owned boat, and sail to the company owned amusement park.

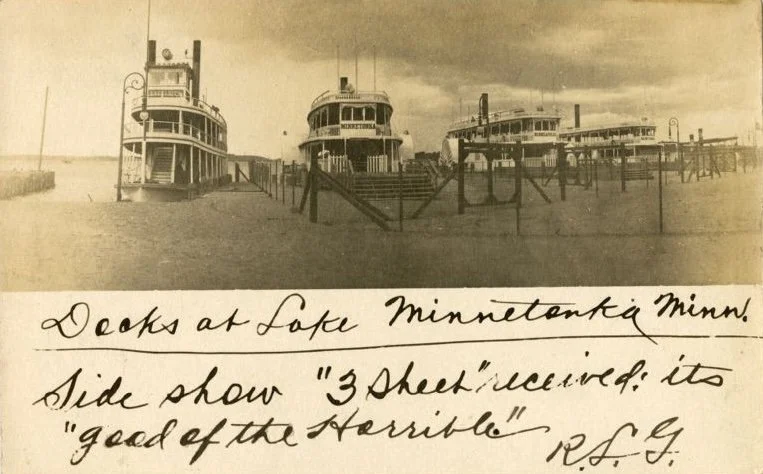

To get all these tourists to the island from Excelsior, however, required much more than the 60 foot streetcar boats could offer. So, again, in 1906 the company launched three more steamers into the lake. Truthfully, they were launched onto the lake, as they were slid out on the ice before the spring thaw. These three steamers were entirely different from the company’s other vessels. Compared against the Streetcar boats these were massive hulks, spanning three decks, 109 feet in length, 35 in width, and intended to carry 800 - 1000 passengers each. Rather than the more modern propeller drive system that the other boats employed, these three ferries utilized a dual paddlewheel system for their propulsion.

Their names were reminiscent of the areas the Rapid Transit company would come to dominate: Minneapolis, Saint Paul, and Minnetonka. Despite their impressive statistics, their first year of service on the Big Island route proved to be a total failure. How could this happen? Engineering on the boat had accounted for the weight of machinery aboard but, when constructed, the weight was nearly doubled. This had effectively sunk the boats into the water and reduced their passenger count to only a few hundred people. To boot, their deep draft caused instability in all three boats. Something had to be done, and quickly, to resolve the issues.

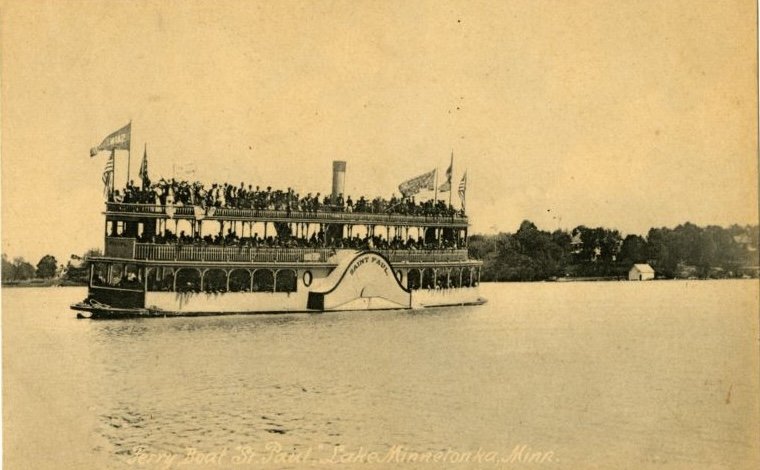

Saint Paul showing a substantial Starboard list & riding along the waterline. c1906

During the winter of 1906, all three boats were hauled ashore, dismantled, and refitted with entirely new hulls. Their rebuilding would see them go from 109’ to 139’ in length and from 35’ to 39’ in width. The overhaul would add roughly a third to their total construction cost. In doing so, their rub-rails were brought substantially higher, sitting roughly a few feet from the waterline. From 1907 to 1911 the three sisters ran successfully, carrying passengers to & from Big Island every 15 minutes.

Steam ferry Saint Paul pulling into Big Island with her new hull. Circa 1910.

Despite the hefty investment taken by the Twin City Rapid Transit Company, the ferries were wholly dependent on the success or failure of Big Island Park. As an attraction, the park proved to be a complete failure. A mix of slumping national tourism, downward ridership trends, and the island’s geographical challenges caused it to lose more money than the company was willing to handle. By the end of the 1911 season, Big Island Park was permanently closed and abandoned. This left Minneapolis, Saint Paul, and Minnetonka with no purpose and an uncertain future. The Rapid Transit Company was no stranger to disposing of unneeded watercraft and decided to take a page from their success in burning the steamboat Excelsior back in 1909. To recreate the event, the company chose Minneapolis as the proper candidate for burning. She, being the largest of the three, would make for the best spectacle.

On August 8, 1912, Minneapolis was towed out to deep water off Big Island and anchored in place. Like her fleet mate before her, her superstructure was coated in kerosene and hull loaded with inflammable debris in preparation for the event. However, unlike Excelsior’s burning, Minneapolis had firecrackers stowed in her hull to create an even greater sight. As the sun settled on the horizon, some 25,000 people arrived to watch the event. 100 privately owned boats drifted in the water and the express boats tooled about in wait for the inevitable. Meanwhile, steamboat Plymouth circled Minneapolis with officials from the Rapid Transit Company aboard. Plymouth donned red lights as a cautionary nod for other motorists to steer clear of the ill fated steamer. Then, at 9:00 pm, a worker boarded Minneapolis and climbed to her upper deck where he began to light torches mounted to her railing. He did the same on her second deck and, upon reaching her gunwale, hopped into a rowboat and quickly left her alone. Flames lapped at her wooden frameworks as she was fully engulfed from stem to stern. Flying high on her mast were blue and white flags donning the steamer’s name which, eventually, were all but devoured by the flames.

65 minutes later, the fire finally reached the waterline. Water began to pour into her hull and she began to settle into the waves with, “a sound that resembled a half audible sigh”. While she descended the water column, the spectating boats sounded their horns as if bidding her farewell. The charred hull of Minneapolis came to rest in some 68 feet of water, her final resting place.

As for her sisters, both Minnetonka and Saint Paul had their upper decks dismantled and hulls sold for various uses around the lake, but never again sailed in their former glory. The Streetcar Company continued to operate their Express Boats for over a decade until, they too, were sunk in the lake. Of the Rapid Transit Company’s fleet of boats, only one would survive them and continue to sail. That being the streetcar boat Hopkins. Perhaps ironically, she also found her end at the bottom of Minnetonka alongside her sisters who preceded her by 23 years.

Read about the sinking of steamboat Excelsior here:

Bibliography of sources:

A Directory of Old Boats, McGinnis, 2010

A Record of Old Boats, Edgar, 1934

Lake Minnetonka’s Historic Hotels, Wilson Meyer, 1997

Minneapolis Tribune newspaper, 12/09/1912

All photos sourced from Minnesota Digital Library archive.