Essential Read! Hotel Saint Louis & the Douglas Family

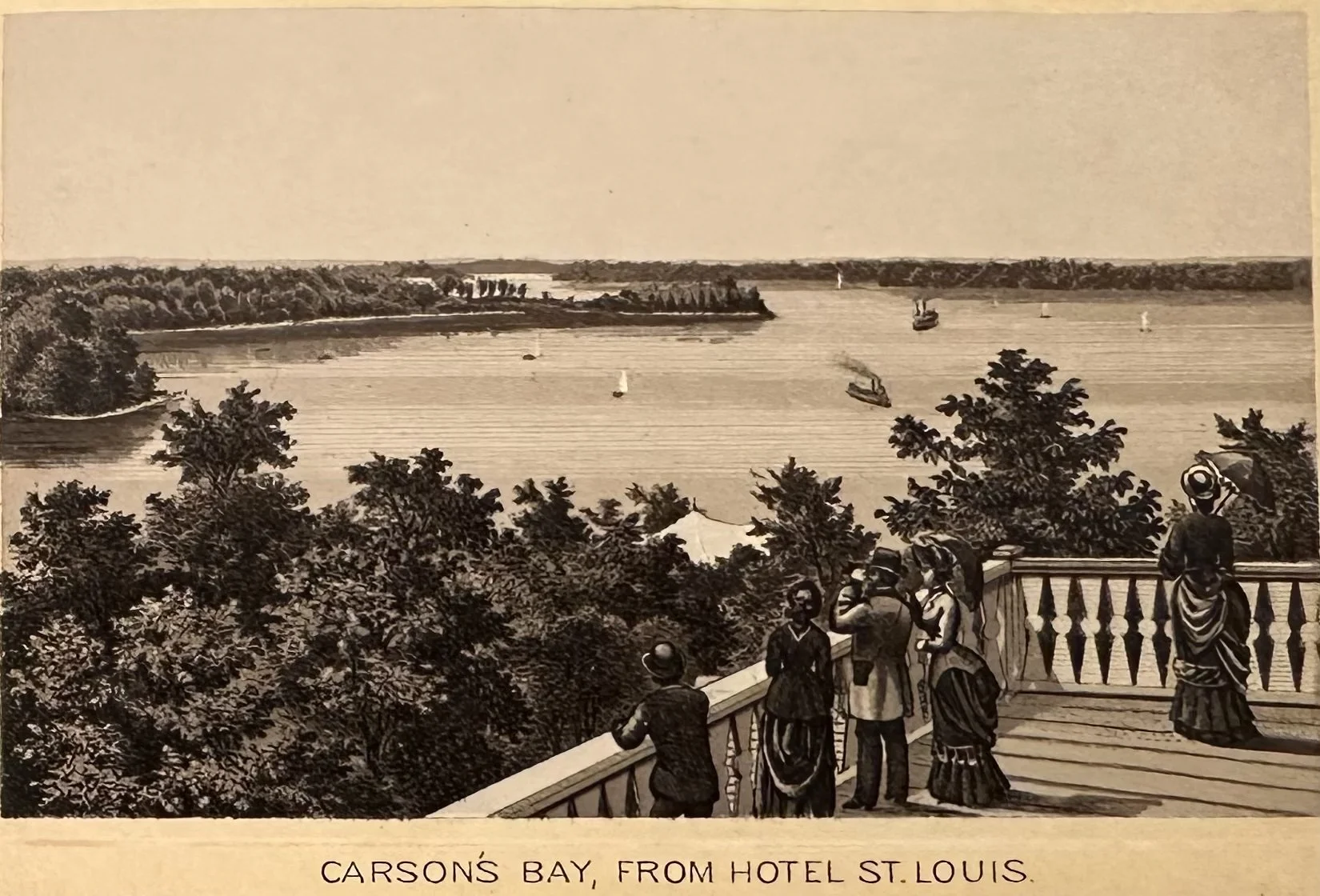

Original 1887 Witteman Bros lithograph by Louis Glaser. Minnetonka Minute Archive

It’s no secret that, for nearly a century, hotels and resorts were an unavoidable feature of the Lake Minnetonka skyline. While not necessarily the first hotel on the lake, the Hotel Saint Louis was certainly the first of the big ones. When considering which hotels were the biggest, brightest, and most glamorous, a few names might come to mind: Lafayette, Tonka Bay / Lake Park, Del Otero, and Saint Louis. Among them, the Saint Louis had the first mover advantage.

Opening in 1879 and boasting over 200 rooms across three floors, Saint Louis featured a size that far outpaced anything ever before seen on Minnetonka. Additionally, each floor was equipped with a bath room, parlor, smoking lounge, and dining room. Despite such amenities, the building’s defining feature was easily its sweeping verandas which offered views of Carson’s Bay and Bay Saint Louis. Truly, it was as stately as possible. After all, it had to be, in order to capture the kind of clientele they were after: wealthy Southerners seeking refuge from their home state’s sweltering summers.

Indeed, they would capture them. Riding the Chicago Milwaukee and Saint Paul railway directly to the hotel’s property were wealthy southerners from cities as far as New Orleans, Kansas City, and (of course) Saint Louis. Many of these patrons weren’t here for a week getaway either. Rather, many opted to stay in the area for the majority of the season. With long term stays in mind, many wouldn’t simply come alone either. Taking the nation-spanning trek north with them were servants and assistants, many of whom were black. For them, management offered separate living quarters in the form of tidy cottages tucked behind the main hotel building. This would also be where black hotel staff would live, if they remained on site full time. In a time of strong racial division, this wasn’t entirely uncommon in the area.

By 1893, the tourism market had severely diminished for the bustling Minnetonka hospitality industry. the 1880’s saw a roaring boom of success and flourishing construction set to meet demand. However, as the United States’ economy slowed into the 1890’s and, again, with the panic of 1893, there was much less business to go around. Not to mention newly expanded railway networks were offering fresh destinations to tourists. In an effort to bolster their bookings and secure profits, Hotel Saint Louis pivoted in a unique way. By hosting Lawn Tennis tournaments, a newer and sportier clientele filled the hotel’s rooms. Naturally, the illustrious nature of the hotel didn’t stop at the court’s edge, with prizes for tournaments reaching upward of $250. While it’s difficult to adjust for inflation, one could safely assume this prize would be $9,000-$10,000 in 2025. Imagine that for a single game of lawn tennis!!

Yet, like many hotels of its era, good times simply couldn’t last forever. As the 20th century rolled in, tourism steadily rolled out of the Lake Minnetonka area. Hotels struggled to keep their doors open and, as a result, were forced to adapt or collapse. While battling the financial hardship the Gibson family, who controlled the property, had been selling parcels of property to developers and individuals.

Then the inevitable finally arrived at the doorstep of Hotel Saint Louis. Southern tourism on Minnetonka had rapidly been replaced by a push from Minneapolis & Saint Paul residents to live on or near Minnetonka and commute to work in the cities. This collision of interests would prove devastating for the major hotel.

1887 lithograph - Rooftop view from the hotel. Minnetonka Minute Archive

The Gibson family saw the writing on the wall and adjusted course appropriately. . . in 1907, after a tremendous sale of the building’s furnishings, the hotel was fully demolished. The property was sold in 1908 to Quaker Oats co-founder, Walter Douglas. Both Walter and his wife Mahala dreamed of a lavish French inspired retreat from their busy lives. Construction would take until 1912 and, when it was nearing completion, the couple would travel to Europe to procure expensive antique furnishings to fill their new home. After their excursions were complete, they’d book passage back to the United States aboard the RMS Titanic.

Roughly 2/3 of the way across the Atlantic Ocean, Titanic struck and iceberg and began to sink. It’s well known that the standard for the time was quite plainly, “women and children first”. As panic began to break out aboard the stricken liner, Walter ushered Mahala to a lifeboat, situated her inside it, and quietly rejected her plea for him to sit beside her saying, “No, I must be a gentleman.” Mahala’s lifeboat was lowered and, as she was rowed away from the ship, Walter continued helping both women and children from the boat’s deck into lifeboats.

When he came upon the final boat as it was being launched he was, again, offered a seat inside. Walter, like many of the other men aboard, rejected the offer and chose to go down with the ship. In the face of certain death, he simply stated, “I wouldn’t be a man if I took a seat while there was still a woman needing to be saved.”

Indeed, he did more than most in those final hours before Titanic vanished into the icy waters of the Atlantic. A week later, Walter’s body was the 62nd to be recovered by the steamer CS Mackay-Bennett. The recovery crew were overwhelmed and faced with the impossible task of recovering several hundred bodies. Unlike hundreds of others, Walter’s body, still dressed in his tuxedo, was identified as having been a wealthy person and so was preserved onboard rather than buried at sea. His body was returned to the United States and buried in Cedar Rapids, Iowa.

Mahala returned to her Deephaven estate, where she lived until her death in 1945.

Walter & Mahala Douglas, sourced from the Douglas Titanic Collection.

Article Sources: